Attack#

Fundamentals#

We are interested in side-channel attacks based on the power consumption of an SoC. Most of these attacks consist on performing a set of common steps :

Acquire the power leakage of crypto-algorithm running

Model the power leakage for various key hypothesis

Correlate the observed power leakage with the modeled power leakage

Iterate the previous steps until the correlation is significant

A key hypothesis consist on fixing the value of several bit groups of the key, supposing that these are the correct. The power leakage is modeled for each key hypothesis. The correlation is computed for each power leakage model.

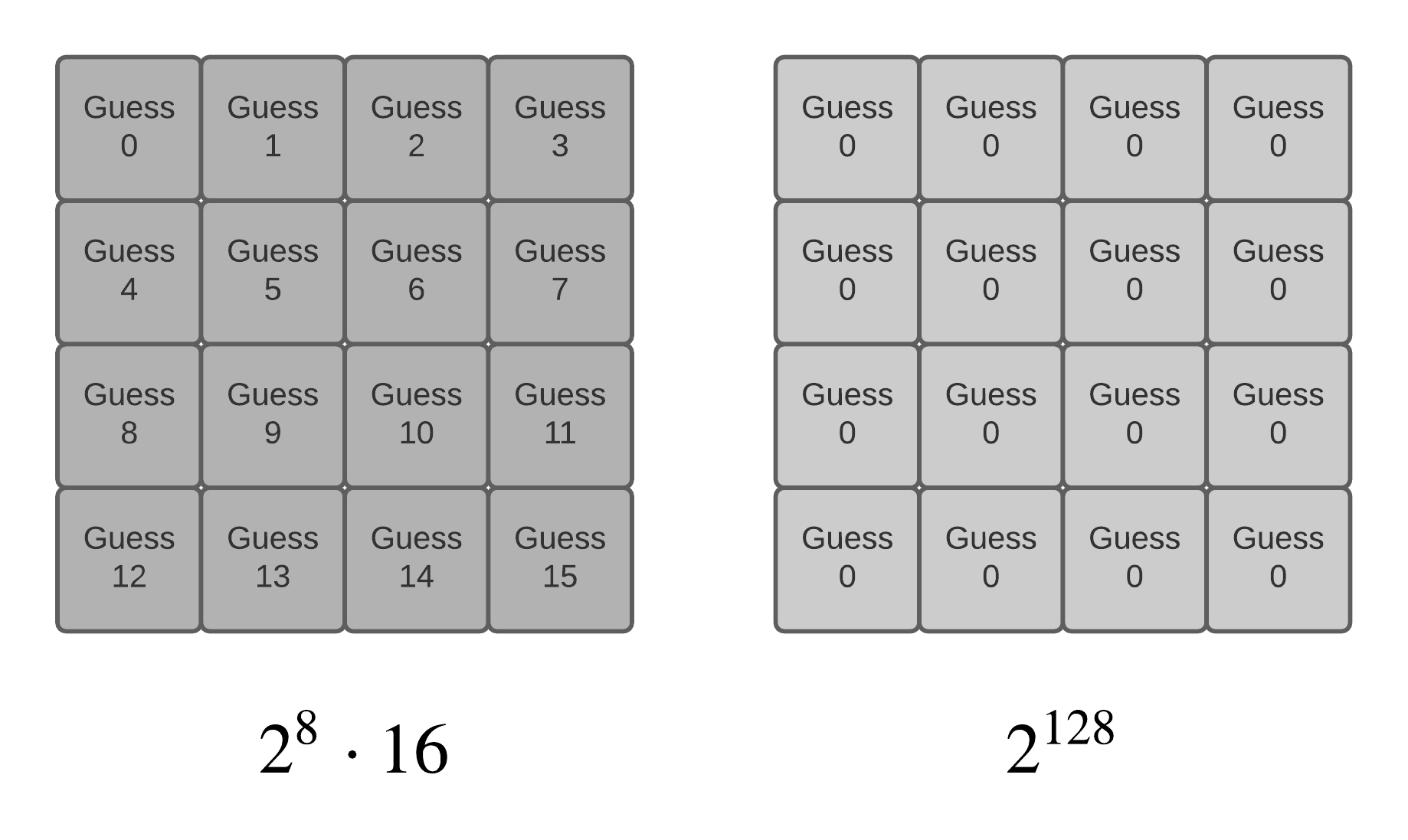

More precisely, the attack is based on a key splitting into bytes or bit groups that can be attacked. It can be characterized as a divide and conquer key inference, we divide the key into multiples part easy to guess by correlation as shown in the figure Key splitting for AES128 algorithm.

Key splitting for AES128 algorithm#

For example with the AES128 algorithm, it leads to formulating \(256 \cdot 16\) key hypothesis. In contrast, an explicit brute force attack in the same conditions would require formulating \(2^{128}\) key hypothesis.

It is not always possible to retrieve the hole key with a side-channel attack. Depending on the chosen leakage model, only several bits can be guessed correctly.

After modeling power leakage for the hypothesis, we use the Correlation Power Analysis (CPA) to produce a guess for the key. The correlation is computed using Pearson’s coefficient defined by :

Where \(X\) is the instantaneous observed power leakage random variable and \(Y\) the modeled power leakage. \(\mu\) denotes the sample mean, \(\sigma\) the sample standard deviation and \(E\) the expectation of a random variable.

The Pearson’s coefficient’s value is in the interval \([-1, 1]\). A negative correlation denotes a inverse linear dependency between \(X\) and \(Y\). A positive correlation denotes a direct linear dependency and a correlation near zero indicates that the two variables are not linearly correlated.

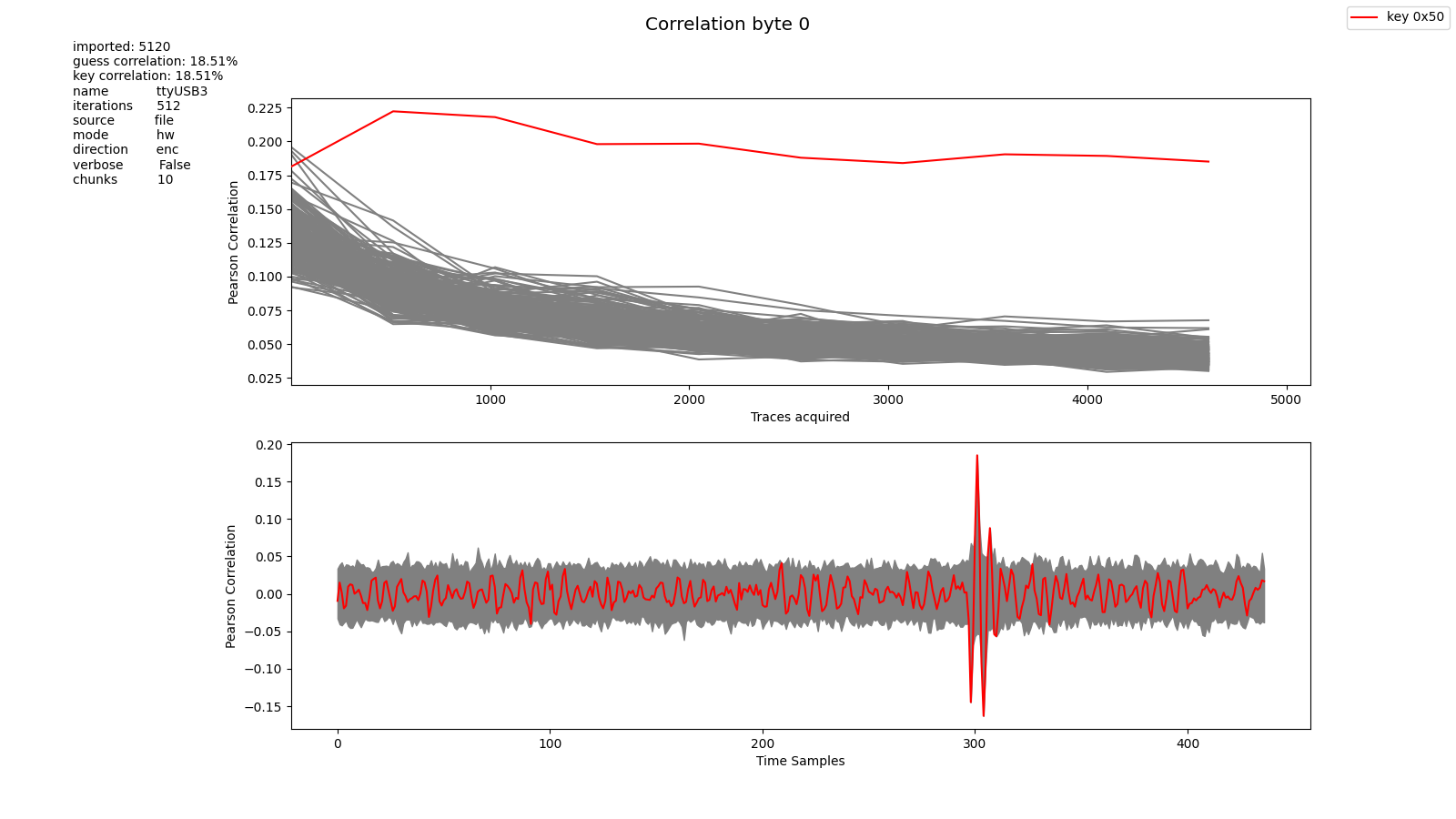

The correlation coefficient depends on time \(\rho_{X, Y} = \rho_{X(t), Y}\). It is computed all along the leakage signals and will peak at a distinctive instant if a strong guess is made as shown in the figure Example of a successful hardware AES128 attack.

Example of a successful hardware AES128 attack#

We consider that the correlation coefficient indicates how good our key hypothesis was. More precisely, we state that if the best absolute value of the coefficient is \(N\) times greater than the second best absolute correlation, the key has been guessed, \(N\) being arbitrary. Otherwise, we acquire more power leakage data in order to obtain a better correlation.

The success condition can be express with the formula below :

Where we defined :

Victims#

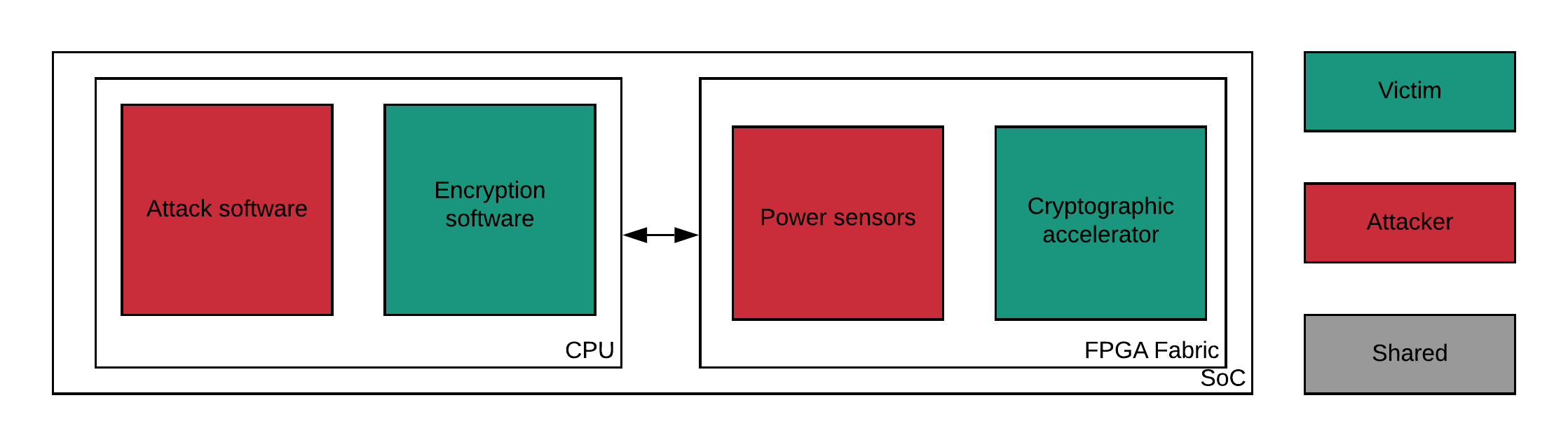

The victims of such a side-channel attack are all the electronic devices that are not protected against power leakages. Since we are performing remote side-channel attacks using FPGA our victim we preferentially will be servers provided with an FPGA fabric that can be shared among multiple servers users.

FPGA based remote-sensors are employed in the framework to eavesdrop the power leakage of a crypto-algorithm running in the SoC.

Therefore, at least two types of targets are sensitive to our attack, the CPU and the FPGA accelerators as shown in the figure Potential victims of our attack.

Potential victims of our attack#

In the first case, the power leakage of the CPU is leveraged. This leakage contains among a lot of noise due to the CPU activity, the information on the crypto-algorithms running.

In the second case, the power leakage of the fabric is leveraged, This leakage is much more significant because the electrical activity is more intense than CPU’s one when crypto-algorithms are running.

Assumptions#

Side-channel attacks works only under several assumptions :

Attacker and victim share the same FPGA fabric

Attacker and victim shares the same CPU

The key remains the same during all the leakage acquisition

Since we attempt to demonstrate the abilities of side-channel attacks, we will not consider the triggering issues. We will assume that the attacker is able to synchronously trigger leakage acquisition with the victim crypto-computations.

Our Setup#

Stages#

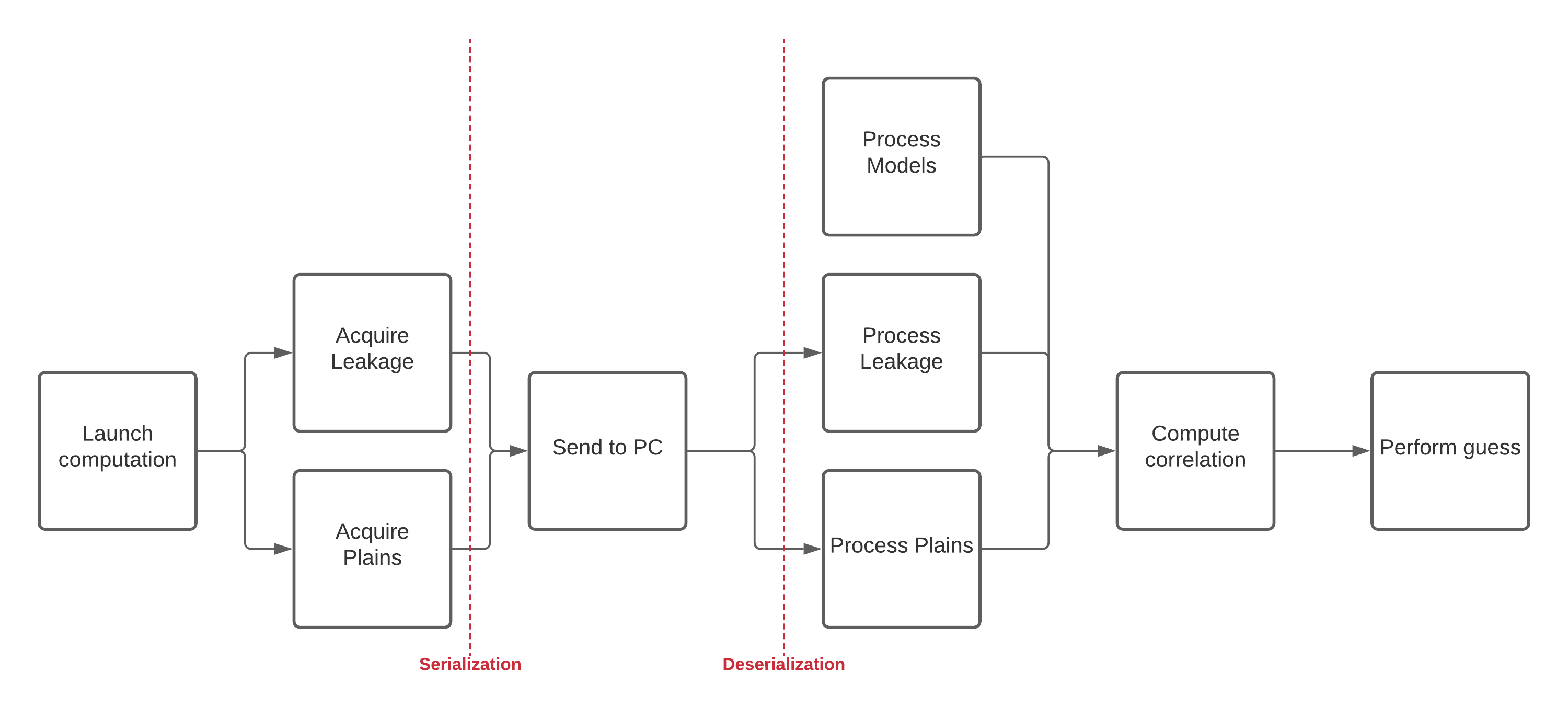

In order to standardize the stages of a side-channel attack we defined a procedure called the attack pipeline. It consists on several steps that will allow to manually or programmatically reproduce this attack. The procedure works for all targets under the assumptions provided above :

Launch sensors acquisition and crypto-algorithm

Wait until crypto-algorithm end

Stop sensors acquisition

Send data via serial port

Correlate data

Guess the key

The pipeline steps are resumed in the figure Overview of the attack steps.

Overview of the attack steps#

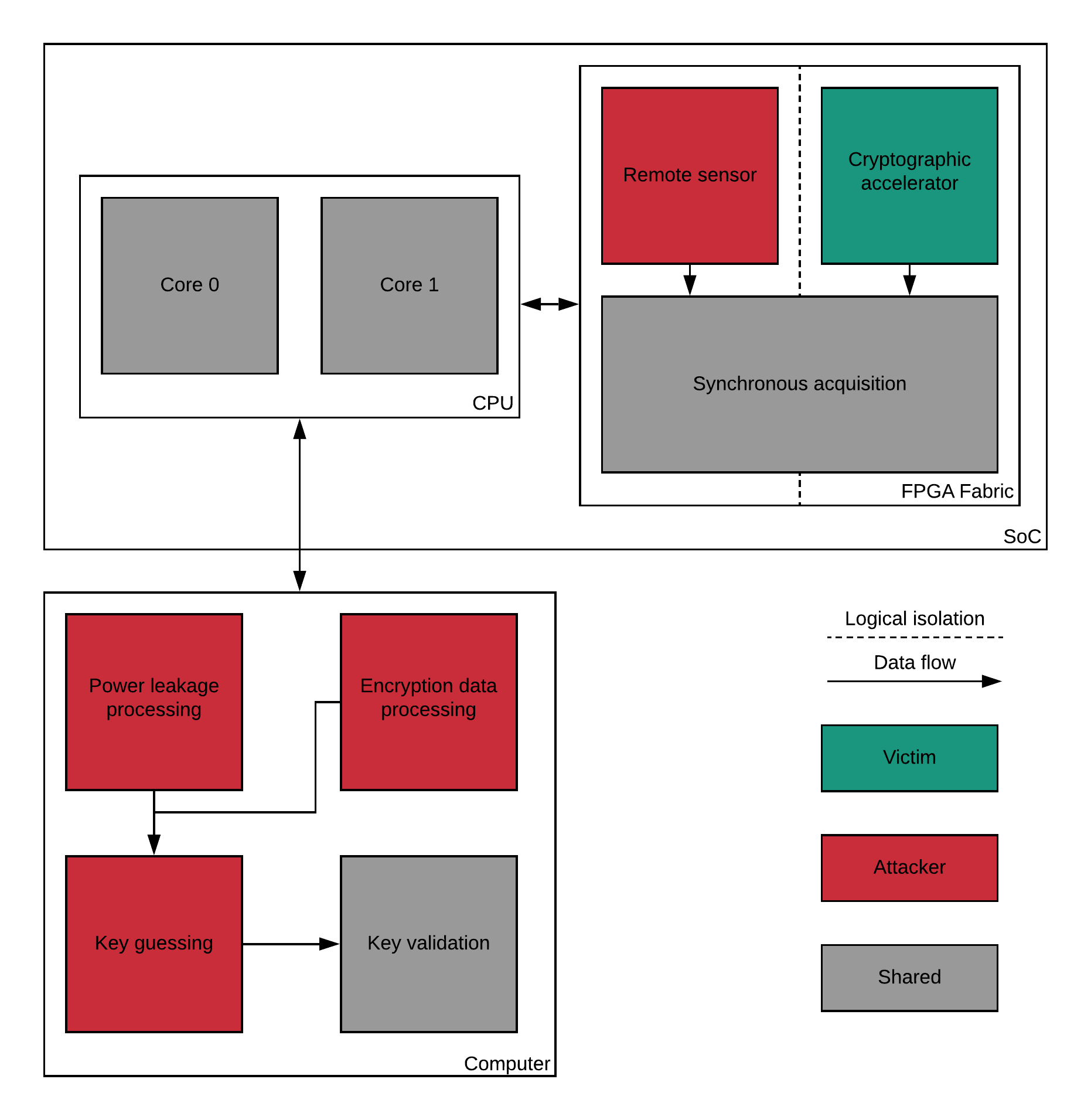

Architecture#

In order to perform successfully the pipeline, we designed an hybrid bench architecture that simulates the remote side-channel attack setup. Our architecture is made to reproduce attacks and to be flexible, the goal being for users to customize the attack bench. We can split the bench into different parts located on the SoC :

Acquisition control : handle sensors acquisition

Sensors : capture power leakage

Victim : perform cryptographic computation

The figure Overview of the bench architecture detail how our architecture implement the attack pipeline.

Overview of the bench architecture#

The acquisition controller is shared so the leakage is captured synchronously with the crypto-algorithm run. This allows to have consistent data among the iterations.

The cores are considered shared even if they can be completely owned by the attacker or the victim. In our most simple configuration, one core is used both as a victim, performing crypto-computation, and as an attacker, communicating leakage and encryption data. More sophisticated configurations separates attacker and victim cores in order to produce a more realistic leakage.

Lastly, the key validation part allows to verify if the attack guess was correct by comparing the original key with the guessed one, which can be performed only if the attacker is provided with the correct key in advance.